Translated into Thai by Teerada Na Jatturas

(To read the Thai version, click the flag icon in the upper right-hand corner of your screen.)

Despite the rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in our everyday life and communications, it is still little understood by much of civil society in Southeast Asia. What exactly is AI? And what are its current applications in the region? How do we relate these new technologies with risks of human rights violations? And what are the possible advocacy strategies?

This is a series of articles on the human rights implications of AI in the context of our region, targeted at raising awareness and engagement of civil society actors who work with marginalised communities, on rights advocacy, and on developmental issues, such as public health, poverty, and environmental causes.

AI Explained

Artificial intelligence is a catch-all term that can mean many things. Indeed, most papers on the topic start off by saying that there is no universally accepted definition of what it is.

Broadly speaking, AI is “the study of devices that perceive their environment and define a course of action that will maximise its chance of achieving a given goal” (World Wide Web Foundation, 2017).

In practical terms, machine learning is the subset of AI that is most widely applied, and it is what we usually refer to when we consider the societal implications of AI.

AI is the study of devices that perceive their environment and define a course of action.

The Internet Society (2017) explains machine learning as such: instead of giving computers step-by-step instructions to solve a problem, the human programmer gives the computer instructions and rules to learn from the data provided. Based on inferences gained from the data, the computer then generates new rules to provide information and services.

In other words, algorithms, defined as “a sequence of instructions used to solve a problem”, generate algorithms. With that, machines can provide solutions to complicated tasks that cannot be manually programmed.

Human Rights Impacts of AI

Scholars from the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society of Harvard University point out that (positive and negative) human rights impacts of machine learning come from at least three main sources:

- Quality of training data: This is known as the “garbage in, garbage out” problem where even the best algorithms will give skewed outputs when the data that it trains on is biased.

- System design: The human designers of the AI systems may incorporate their own values on the design, such as prioritising certain variables to be optimised, over others.

- Complex interactions: The AI system may interact with its environment in a way that leads to unpredictable outcomes.

The same study provides six use cases on decision-making with AI, from criminal justice to healthcare diagnostics. Possible impacts are mapped onto the human rights framework, which gives a concrete depiction of specific rights affected by AI use in different fields.

It is important to note also that the efficacy of AI varies according to different functions, and the positive results of some use cases are sometimes overly exaggerated.

Inaccuracies in prediction results can be devastating to human life and dignity.

In a presentation titled “How to Recognise AI Snake Oil”, Professor Arvind Narayanan from Princeton University argues that while AI has been applied successfully in the areas of perception (such as content identification, face recognition, and medical diagnosis from scans), usage in predicting social outcomes (such as likelihood of criminal activity or job performance) is deemed to be “fundamentally dubious”.

This is something to keep in mind, as inaccuracies in prediction results can be devastating to human life and dignity.

The Southeast Asian Context

Not much has been written about human rights concerns of AI usage in the context of Southeast Asia. While AI ethics and principles have been heavily discussed and debated, most of these conversations happen within developed countries (and China) where the technologies originate.

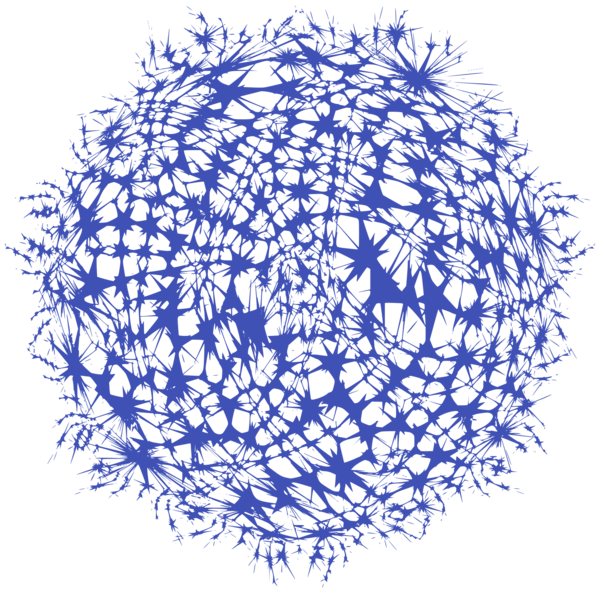

Here is a useful visualisation that sums up 32 sets of AI principles, or guidelines for ethical AI, which represent international and transnational perspectives from governments, companies, advocacy groups, and multistakeholder forums. None of these perspectives come from Southeast Asia. This is problematic because some challenges brought by AI to this region may differ from those faced by other regions. Here are some considerations to set the scene:

Digital authoritarianism through AI:

The latest report from Civicus Monitor shows that none of the eleven countries in the region received a rating higher than “obstructed”. None of the eight countries assessed in the Freedom on the Net report by Freedom House (2018) obtained a “free” status in Internet freedom. What this implies is that civil society in the region is often cautious about the state applying AI in ways that restrict civil and political rights, such as digital surveillance. The human rights impacts of AI, therefore, go beyond inherent problems of the technology (as mentioned in the above section) and cover the weaponisation of AI to restrict freedoms.

The human rights impacts of AI go beyond inherent problems of the technology.

...exclusion from datasets is a larger concern than potential illegitimate use of data.

Underrepresentation in datasets:

In a session during the Internet Governance Forum 2017 on “AI in Asia: What’s Similar, What’s Different?”, it was pointed out that in certain Asian countries (examples given were India and Malaysia), exclusion from datasets is a larger concern than potential illegitimate use of data. This runs counter to data protection and privacy narratives coming from the West. The lack of quality data coming from the region is also considered “a major challenge” for machine learning startups, which are forced to use datasets coming from US and UK to train their machines, leading to data biases that don’t work in local contexts.

Socioeconomic impacts of AI:

A McKinsey report (2017) notes that AI has the potential to automate about half the work activities (equivalent to more than $900bil worth of wages) in the four biggest economies of ASEAN: Indonesia (52%), Malaysia (51%), the Philippines (48%), and Thailand (55%). It has also been noted by the World Wide Web Foundation (2017) that the price of capital, not the price of labour, will determine the location of production of AI in the future. The socioeconomic impacts will hit women disproportionately in office and administrative functions.

AI has the potential to automate about half the work activities.

...lack of technical capacity is another barrier in participation in governance.

Participation in AI Governance:

The US and China are the main global players when it comes to AI, even though there is AI activity in each member state of ASEAN (McKinsey Global Institute, 2017). Being distant geographically and politically from the power centres of technology, the peoples of Southeast Asia have little say in AI design and governance, and little control over their personal data and digital trails when using applications offered by the US and China. The lack of technical capacity is another barrier in participation in governance, as indicated by my previous research on the digital rights movement in Southeast Asia (2019).

The above points are not exhaustive, but provide some context of the region when it comes to concerns about AI and machine learning. It is clear that AI will bring major disruptions to the region in coming years, and civil society will need to follow the technological advancements closely to understand the opportunities and risks it will bring to our work.

The next articles in the series will go deeper into the topic of AI policies, applications, and implications within the region. As part of this project, we are building an annotated reading list that will continue to be updated in the coming months– which you can also check out for further reading.

Dr. Jun-E Tan is an independent researcher based in Kuala Lumpur. Her research and advocacy interests are broadly anchored in the areas of digital communication, human rights, and sustainable development. Jun-E’s newest academic paper, “Digital Rights in Southeast Asia: Conceptual Framework and Movement Building” was published in December 2019 by SHAPE-SEA in an open access book titled “Exploring the Nexus Between Technologies and Human Rights: Opportunities and Challenges in Southeast Asia”. She blogs sporadically here.

The views expressed in this post do not necessarily reflect the views of the Coconet community, EngageMedia, APC, or their funders. Copyright of the article is held by the author(s) of each article. Check out our Contribution Guidelines for more information. Want to translate this piece to a different language? Contact us via this form. This publication is licensed with Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.